Mary

Creasonís Aviation

| |

|

|

Mabel Rawlinson was a beloved daughter to Nora Belle Berden and William Winthrop Rawlinson. She was little sister to Margaret, John, and Georgian, and big sister to Woody, Jean and Mary. Mabel was a college graduate, a lovely, lively and witty young woman, a pilot, and a heroine, who sacrificed her life while serving her country in World War II. Her parents and many friends suffered such loss when Mabel died at just age 26. Her brothers and sisters never stopped missing Mabel's smiles, thoughtfulness and fun-loving enthusiasm; Mabel's vitality seemed so absent from all family gatherings in the 60 years since she died. Mabel was born in 1917 in a pine tree forest in Greenwood, near Dover, Delaware. In 1925, at age 8, she and her family moved near Blackstone, Nottoway County, Virginia, where they lived a simple rural life down a red clay country road called Cellar Creek Road. Mabel helped her mother with the gardening, housework, sewing, cooking and baking. There were animals to feed, books to read, talent shows, church activities and outdoor adventures. During the Great Depression, Mabel's mother supported their family with her rural schoolteacher's salary. It was the early 1930s. Mabel hoed and raked in the familyís cultivated fields, fed the chickens, socialized with friends and made good grades in school. After graduating from high school in Virginia in 1935, Mabel moved to Kalamazoo, Michigan, where her aunt, Eleanor Rawlinson, was an English professor. Living with her aunt, Mabel attended college classes and worked in the college Health Service. Graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1939 from Western Michigan University, Mabel worked in the Kalamazoo Plating Works and the Kalamazoo Public Library. In 1940, she received her first flying lesson and returned to Western Michigan University to take post-graduate civilian pilot training courses, then recently opened to women. On October 31st, 1940, Mabel soloed for the first time. While still working at the library, she joined the Aviatrix Club, achieved her private pilot license and spent most of her free time at the Kalamazoo airport. By 1941, Mabel had become co-owner of an Aeronica Chief airplane in Kalamazoo. When the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and the US entered World War II at the end of 1941, the government initially banned all private flights for national security reasons. Determined to stay in the air, at the end of 1941, Mabel and other Kalamazoo pilots promptly formed the Civil Air Patrol in Kalamazoo. That next year, 1942, was a great year for Mabel - she was flying her Aeronica Chief every week and proudly wearing the uniform of the Civil Air Patrol. It was around September 1942 that word reached Kalamazoo that the Army Air Corps would be recruiting female pilots to assist in the war effort. The demand for male combat pilots and warplanes had left the Air Transport Command with a shortage of experienced pilots. General Henry "Hap" Arnold, Commanding General of the Army Air Forces, approved a program that would train a large group of women to serve as ferrying pilots with the training school placed under the direction of Jacqueline Cochran. These women would be trained to fly all of the US warplanes and would assist with ferrying planes from factories to bases, towing targets for ground troop practice and training new pilots. These new volunteer female pilots would make it possible for male pilots to relinquish their stateside duties and assist in war efforts overseas, where they were greatly needed. So, 1,857 young women pilots from all over the United States quit their jobs and left the safety of their homes and families to go to Texas. They traveled by car, bus, train, or by plane. Some hitchhiked and all paid their own way to get there. The women joined up with the Army Air Forces because they loved to fly and because their country needed them. Mabel reported on January 15, 1943 at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas, for her Army Air Force pilot training. Excerpted from a letter she wrote to her sister Georgian, April 18, 1943, Mabel said, "It began to occur to me if I'm going to write you while I'm still in the 319th Army Air Forces Flying Training Detachment, I'd better start. One of my three roommates is home packing up her things today - washed out, she is. Had her Army check ride yesterday, and the Lieutenant recommended for her elimination. I'll be having my next Army ride any day now, so maybe I'll be packing up too... If I should get through (our class graduation in about 2 months), I'll have a 10-day vacation before I go to my post (and if I have my choice, it'll be California), and a bunch of us are planning to go down to Mexico. I had my first instrument time today. It's fun but a lot of work. The class ahead of us is having night flying now. It must be beautiful up there these nights, the moon is shining. Newsreels are going to be made of the occasion (of our graduation)... Maybe you'll see the newsreel in Baltimore. My latest (boyfriend) is named John... He's 6'1", 200 lbs, a couple of dimples and exceptionally nice. I think he's overseas now though. He's in the air corps, combat unit, also he's an engine specialist. I went to see him one weekend in San Antonio. We had a good time. Went all through the Alamo, etc... Guess I'd better write home now. If I don't write every week, Mother thinks I've cracked up for sure. Write. So long, Mabel." After receiving her wings and completing her basic training in the WFTD Class 43-W-3 at Sweetwater, Texas, July 1943, Mabel took a short R&R in Mexico with friends. Then, following Army orders, Mabel reported to Camp Davis Army Air Field in North Carolina for advanced training. On August 5, 1943, the WAFS and the WFTD were merged and were re-designated the Women Airforce Service Pilots, or WASP. Camp Davis was her last post.

Mabel Rawlinson soon became one of the very special women who served and

died as pilots for the Air Force in World War II. It was at Camp Davis on

August 23, 1943 that Mabel lost her life when her airplane crashed and was

consumed by flames. Since WASP were technically considered volunteer

civilian pilots and not Air Force pilots, no monetary compensation was

available to the Rawlinson family for her funeral expenses. The other

female pilots at Camp Davis pooled their extra money and assisted in the

expense of transporting Mabelís casket back to Kalamazoo for burial.

There, her casket was draped with an American flag and the Kalamazoo Civil

Air Patrol honored her with buglers, fly-overs and solemn gun salutes.

Mabel was one of 38 military women who lost their lives serving as WASP

during the duration of World War II. WASP were not given full military

status until many years later, many decades after WWII. Today, a monument

at Sweetwater, Texas, commemorates their service to the Air

Force. According to the report, take-off and flight were normal until just before they started to land. In addition to the statement from the instructor, there were two other witness statements concerning the final moments of the flight. Frank J. Fitzgibbon, WO (Jg), was standing on the ramp in front of the hangar when the plane flew over during its attempted landing. He noted that based on "the sound and appearance of flames, the engine was operating on an extremely lean mixture. In my opinion, the airplane was not on fire, and crashed with the engine still operating." Staff Sergeant John A. Ross stated that while cleaning the day room, he "heard a plane overhead missing badly. The plane seemed to be (extraordinarily) lit up by flames coming from the exhaust stacks." According to 2nd Lt. Robillard, who was seriously injured during the crash, "We were circling 2,000 feet at South Zone at about 2100. The tower called and told us to shoot a landing on Runway 4. She entered the pattern normal way at 1100 feet and cut gun to let wheels down. Soon it seemed something was wrong. I felt the throttle moving back and forth and realized the engine was dead. By that time, we had 700 feet and were across runway and then were turning to the left. I took over and told the student to jump. I then shouted at the student to jump. I had little time to look and see if she jumped. Somehow I knew she hadn't. I attempted to bring the plane in for a crash landing on the end of Runway 4. The next thing I felt the airplane shudder and I remember no more." The AAF report summarized these

statements and possibly others with the following: "Halfway through the

first 90 degree turn to the left the safety pilot took over and attempted

to bring the plane in wheels down. He ordered the Woman Pilot to jump. He

finished the first 90 degree turn, flew an abbreviated down wind and base

leg, and was trying to round out a turn on to final approach when the

plane crashed into the trees from a half stall in-turn at low altitude.

The plane broke into halves at the fuselage at the point of the rear

cockpit. The safety pilot was thrown clear but the plane burned. The woman

pilot did not jump and was burned to death strapped in the cockpit. The

wrecked plane rests about 300 yards from the end of Runway 4. A wide

drainage ditch and jungle like trees and swamp undergrowth handicapped

rescue efforts." There is no mention in this report of the faulty latch in

the front cockpit where Mabel was seated. This faulty escape latch is

referred to in other WASP research literature. In a documentary film interview, a former WASP, Dora Dougherty Strother, says, "Mabel Rawlinson's death at Camp Davis. I don't know exactly what it could be attributed to. I did not go out to the crash scene, but the fire was intense. They could not get Mabel out and she burned. It was a very traumatic time for all of us there. I remember there was an old nurse who came over to our barracks and she had a couple bottles of beer and she sat on the end of the barracks out there watching the fire. Drinking her beer and singing old hymns; "Nearer My God to Thee", "Shall We Gather at the River" and in a deep sort of whisky tenor, and just thinking the thoughts that we all thought. Now I think when you join the military you obviously go through a mind set that you are prepared for something like this. This was the first time that I had seen a friend die. So it was a trauma for me and I think for all of us." Dora Strother continued, "When the enlisted men on the flight line of the 3rd Tow Target Squadron at Camp Davis, North Carolina, heard that women pilots were coming to learn to tow targets, they all immediately requested transfer." Another WASP at Camp Davis, Marion Hanrahan, wrote: "The men pilots resented us primarily because, should the women succeed in replacing them, it would mean combat duty. Most were not qualified to fly in this capacity so it would be in ground troops... I was at Camp Davis five months and flew several missions. I knew Mabel very well. We were both scheduled to check out on night flight in the A-24. My time preceded hers but she offered to go first because I hadn't had dinner yet. We were in the dining room when we heard the siren that indicated a crash. When we ran out on the field we saw the front of her plane engulfed in fire and could hear Mabel screaming. It was a nightmare." The women pilots were, in fact, placed in harm's way by towing targets for training ground troops. Since these ground troops were "in training", it is certainly possible that they could miss their targets. It is also true that most of the female pilots encountered overt resentment from some of the male pilots that did not want to be shipped overseas. However, Mary Creason, Mabel's youngest sister, does not believe that these occurrences explain the cause of Mabel's accident. Mary has investigated the mishap thoroughly and she believes that the cause is related to the inferior equipment that the WASP were using. Mary Creason writes, "I have done extensive research and have discovered the reason for the accident. The aircraft developed mechanical problems after take off from the Camp Davis runway, and it was necessary for Mabel and her instructor, who was checking her out at night, to come back for landing. Recently I talked with another WASP who was eyewitness, in fact, she was supposed to follow Mabel in her aircraft, but had to return to the ramp because of an aircraft problem. I have this documented if anyone wants it. I remember well receiving the call in the middle of the night on August 23, 1942. A loud voice read my mother and me a telegram, 'We regret to inform you that your daughter has been killed . . .' We were told by Bertha Link who accompanied Mabel's body home that the aircraft caught fire in the air. Last year I talked to the widow of the flight instructor, and she said he had talked about the crash a lot. He said there was nothing to do but follow procedures and 'take it in.' Mabel was in no way at fault. What was at fault was the latch - yes, the latch could not be opened from the inside of the aircraft - there was no way Mabel could have exited. It has been my hope always that she was unconscious from fumes prior to the crash. Mabel was a professional secretary for Flora Roberts at the Kalamazoo Public Library (KPL) and she sang only for the church choir and her own (and our) entertainment. She and her mother (Nora Berden Rawlinson) signed up each year for the Kalamazoo community production of 'The Messiah.' (Knowing I couldn't carry a tune, I was not invited to participate.) I worked at the KPL also while Mabel was employed there - she was a highly respected member of the staff. I stayed with KPL part time throughout my college years, and had planned on going on to get my masters in Library Science. Then I got interested in two things - Bill Creason and flying. So long, library work. I've read them all (all the books about the WASP). Sadly, the authors did not do their homework (about Mabel)." Jacqueline Cochran, Director of

the WASP, sent this telegram to Mabel's family, in August 1943, "I hope

this will convey to you how deeply we all feel about Mabel's accident. May

God give you strength to find comfort in the fact that when she was called

to make the supreme sacrifice, she was serving her country in the highest

capacity permitted women today." On January 18th, 1945, General Arnold wrote this to Mabel's mother, Nora Belle Rawlinson, "Dear Mrs. Rawlinson, During the Army Air Forces' tribute to the Women Air forces Services Pilots at Sweetwater, Texas, on 7 December 1944, a plaque was dedicated to the memory of those WASP who died while serving their country... Realizing that you may not have an opportunity to see the plaque and knowing that you would treasure such a memorial to your daughter, I am enclosing a photographic copy of it... There is little I can say to console you in the loss of your daughter, but I trust the memory of her devotion to her country will bring some measure of solace. And I urge you to remember that she... left a brave heritage to America - heritage of faith in victory and faith in the ultimate freedom of humanity. My heartfelt sympathy is extended to you." A Memorial Booklet "Thirty Eight

American Women Pilots", published by the Texas Womens University Press,

says, "Mabel Virginia Rawlinson was born... on March 19, 1917. She

graduated from Western Michigan College of Education, Kalamazoo, Michigan,

and served as secretary for Kalamazoo Public Library. She enjoyed singing

and sports, especially tennis. She served as Sergeant in Civil Air Patrol.

She belonged to the Aviatrix Club of Kalamazoo. When she joined the WASP,

she gave her share of an Aeronica Chief to her sister, Mary Rawlinson.

Mabel loved life and people. She was vivacious and loved to write. A

master of words, she no doubt would have been an author if she had

survived WWII. While serving with a tow-target squadron at Camp Davis Army

Air Field, North Carolina, Mabel crashed with her instructor in an A-24 on

August 23, 1943. Mabel was buried in Kalamazoo, Michigan. She had six

brothers and sisters in Virginia, Maryland, Washington, Michigan and West

Africa." Ellis continues, "No one held head

higher than Nora Rawlinson as we learned that Mabel was doing night

flying, that she was piloting bombers, that the accident which brought her

death was no fault of hers, and that as a good soldier she had taken the

risk, played her part, and met her fate. The service, the first military

funeral for a woman in Kalamazoo and, possibly, in Michigan, began with a

simple gathering of friends. Mr. Perdew and Mr. (William Y.) Pohly of the

Methodist Church spoke and prayed; there was very gentle music. Few of us

cried but our hearts were full, too full of pride, to pay tribute in

tears. Men in uniform carried the casket to the hearse; both men and women

in uniform stood at salute at the cemetery; we counted nine planes which

circled over the burial place and then slipped away one by one; the firing

squad gave their round of farewells; the flag was folded and given to your

mother, and we came away. They were grand, sacred days of which you would

be glad to tell your children's children. They were days, which help us to

understand that the big things of life are good things and, having come

close to them for a little while, we shall never so easily be trifling

again... The big thing is that Mabel, who had dwelt among us, is

remembered at the places where she was: Western (Mich. U.) and the part

she took; the Health Service (WMU) where she gave of her loyalty and good

cheer; the (Kalamazoo) Library where her germinating hope for flying came

into fruition; Scrub Oak where she ranged the woods and raked leaves last

fall; the camp where she took her last flight and left a lingering

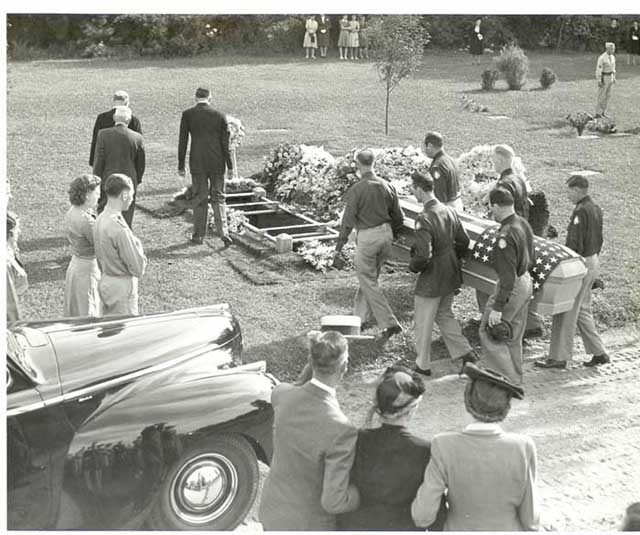

memory." Pictured below: Camp

Davis WASP with Mabel Rawlinson standing on far left.

Pictured above: Mabel's August 1943 burial in Kalamazoo. Her father, mother and sister Margaret are standing in the foreground as the casket passes. Behind them is a long procession of colleagues, family and friends. Those interested in learning more about Mabel Rawlinson, American

hero, and other WASP pilots, can consult our links page under the heading

of WASP.

|

Pictured above: Mabel as a child in Greenwood, Delaware, circa 1920

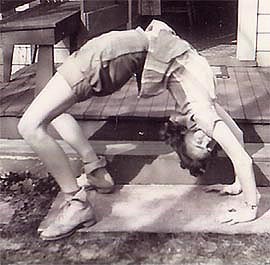

Pictured above: Mabel doing gymnastics, at her aunt's country cottage, Nunica, Michigan, circa 1935

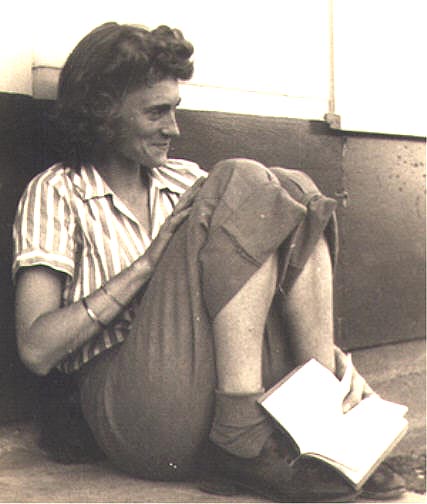

Pictured above: Mabel as a college student, circa 1937

Pictured above: Mabel Rawlinson at Kalamazoo Airport 1941

Pictured above: Mabel in 1942, before joining WASP, shown here in her Civil Air Patrol uniform

Pictured above: Mabel V. Rawlinson, WASP, 1943

Pictured above: Mabel V. Rawlinson, WASP, at Camp Davis, 1943 | |