December 14. 2002 6:01AM

Pioneer female pilot to share

story

|

| ZOOM |

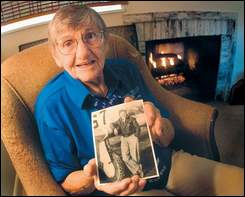

(ROB C. WITZEL/The Gainesville Sun) |

Gainesville resident Kaddy Steele will be heard

on National Public Radio's "All Things Considered" next

week, discussing her experiences as a World War II pilot

in the Women Airforce Service Pilots program or WASPs.

The program was activated after a shortage of male

pilots left a need for female pilots to carry out

various missions.

|

|

| "The WASPs" at a glance |

n WHAT:

A

22-minute radio documentary.

WHEN:

Will air on NPR's "All Things Considered"

on Wednesday.

WHERE:

The program can be heard in Gainesville on

WUFT-FM from 5 to 6:30

p.m. | | Ashley

Rowland

Sun staff writer

rowlana@gvillesun.com

Gainesville resident Kaddy Steele served in

the WASPs in World War II.

or some women, it was a chance to join in the

groundswell of patriotism during World War II. Others saw it as a

way to take revenge for husbands or brothers killed by enemy

fire. or some women, it was a chance to join in the

groundswell of patriotism during World War II. Others saw it as a

way to take revenge for husbands or brothers killed by enemy

fire.

For Kaddy Landry, a 24-year-old from a tiny Michigan

town near the Canadian border, it was a chance to sit behind the

controls of a top-of-the-line aircraft.

"I knew that never

again in my lifetime would I get an opportunity to fly those

airplanes," she said.

Now married and named Kaddy Steele, the

Gainesville resident was one of 1,074 women who served in the Women

Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs) - a wartime program that enlisted

women on the home front to train and aid male pilots who would

eventually fight overseas.

Steele, a UF graduate and former

employee, will be featured in a documentary Wednesday on National

Public Radio.

Producer Joe Richman interviewed about 20

former WASPs at their biannual reunion in Tucson, Ariz. He said the

women - now in their 80s and 90s - still get excited talking about

the speed of the planes they flew.

"All of these women are

just strong, kick-ass, powerful women," he said. "Obviously this was

only two years of their life, but it was just a bubble of

opportunity."

Steele learned to fly during her senior year at

Northern Michigan University after she joined the Civilian Pilot

Training Program.

The program, started before World War II,

was meant to encourage young men to join the military. But a woman

challenged the admission requirements in court, and the program was

required to admit one female per 10 males.

Northern

Michigan's athletic director recruited Steele, a "tomboy" who loved

to swim and ski, to join the school's CPTP. She also got two hours

of credit for participating.

"I had only seen two planes in

my life, and I was 21 years old," she said. "After the first couple

of rides, I was sold."

Call to duty

Steele took a

teaching job in a small Michigan town after she graduated.

She resigned the day after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and took a

high-paying job testing equipment in a defense plant.

In

early 1943, she received a telegram ordering her to report for pilot

training.

That May, Steele began a year-and-a-half stint with

the program. She and other WASPs ferried planes between bases, broke

in new planes just off the production line, and participated in "war

games" to help train men who would eventually face enemy

aircraft.

"Every pilot that was in World War II didn't fly in

combat. It took 12 to 14 utility pilots to keep one pilot in

combat," she said, adding that the women were not officially

considered part of the U.S. Air Force, and were forced to pay for

their own transportation to training camp and buy their own

uniforms.

Even though the WASPs never faced enemy fire, their

jobs were still dangerous. Thirty-eight women died in accidents,

some caused by engine failure or mid-air collisions, while on active

duty.

In an era where women worked as teachers, nurses or

librarians - if they worked outside the home at all - many men found

it degrading to be working alongside a female.

"Our problem

wasn't with the men we worked with every day, who were our age. The

top brass were the ones who didn't want us in there," Steele said.

"They did everything they could to keep us from getting the flying

jobs we would have liked."

The program was deactivated in

December 1944, as men returned from combat to take their

spots.

A turning point

For Steele, who had drifted

between schools during her college years, serving as a WASP was a

turning point.

"It made me realize if I really wanted

something bad enough, I could do it," she said. "I think for all of

us, it was the high point of our life - bigger than going to

college, bigger than getting your first job, bigger than getting

married."

Women didn't fly in the military until 37 years

later. And the former WASPs weren't awarded veteran status until

1978 - too late for many of them to enjoy military insurance

benefits or the GI Bill, which provided higher-education tuition for

veterans.

In the late 1940s, Steele performed acrobatic

maneuvers with an air show for 2 1/2 years, but she said there were

few civilian pilot jobs for women.

Now retired as an

associate director of UF's Office of Instructional Resources, Steele

still gives speeches about her days as a pilot. And last month, she

got to fly a restored B-25 at a Veterans Day celebration, nearly 60

years after she last piloted one of the aircraft.

"I never

dreamed I'd get a chance to do that," she said. "I was very

surprised I remembered that much about it."

Ashley Rowland

can be reached at 374-5095 or rowlana@gvillesun.com.

|